In 2012, we did a television show to identify the greatest Indian after Mahatma Gandhi (post 1947). The winner by some distance was Babasaheb Ambedkar; Jawaharlal Nehru just about made it to the top 10.

Nehru and Ambedkar, two great sons of this country, separated by just two years in birth. Tomorrow the 125th birth anniversary celebrations of Nehru will wind down while Ambedkar’s quasquicentennial will culminate in a grand celebration in April next year.

The Congress has dotted Delhi’s bus stands with posters of Nehru, the Rajiv Gandhi foundation has held a seminar on Nehruvian values but there is little else to mark the occasion.

By contrast, every political party is planning to make a big splash on the Ambedkar anniversary. Mhow, his birthplace, is expected to see a massive congregation: From the BJP to the BSP, from the Congress to the Republic Party outfits, every political party will be seeking to appropriate him.

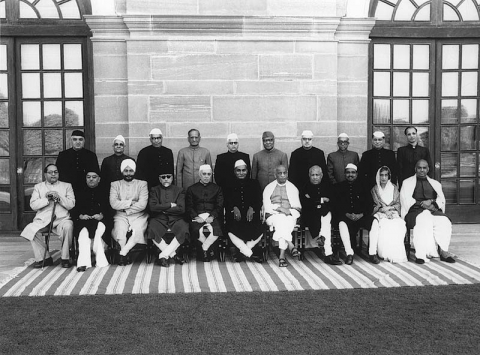

In life, Nehru towered over all his contemporaries, especially in post-Independence India after the passing away of Sardar Patel in 1950.

Ambedkar spearheaded the drafting of the Constitution, was an admirable jurist, reformer and intellectual, but like so many others of the generation was dwarfed by Nehru’s charisma. The first prime minister was venerated by millions of Indians in his lifetime: Chacha Nehru was the original Indian hero.

And yet, the last decade has seen the roles being reversed: Now it is Ambedkar who is lionised while Nehru is subject to calumny.

What explains the rise of Ambedkar and the decline of Nehru after their death?

The most obvious reason would be that Nehru, unlike Ambedkar, is seen to offer a sharp ideological challenge to the Sangh parivar, the rising force of Indian politics. Nehru had a visceral hatred towards the brotherhood in saffron, who he was convinced would create a ‘Hindu Pakistan’.

This uncompromising approach to what he saw as ‘Hindu communalism’ meant that he was bound to attract the ire of those who saw Nehruvian secularism as a wishy-washy commitment to ‘appeasing’ the minorities in the name of safeguarding their interests.

Then, be it Partition, Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir or his belief that “dams were the temples of modern India”, the Sangh and its supporters were convinced that Nehru represented an anglicised elite that was disconnected from what they perceived as the dominant Hindu religio-cultural ethos of this country.

Now, in power, the BJP wants to undermine Nehru’s legacy if only to extract revenge for the years when the Nehruvians dominated the political discourse.

The rise of Narendra Modi has only accelerated this process: The Prime Minister has chosen to deify Patel with a grand statue and a ‘Run for Unity’, he has ordered the de-classification of the Netaji files and has eulogised Lal Bahadur Shastri. But he has chosen, deliberately or otherwise, to ignore Nehru’s contribution.

Even at the much-hyped India-Africa Forum Summit in October, Modi conspicuously chose not to even mention Nehru’s role in furthering India-African amity: It was left to the visiting African heads of state to pay tribute to the Nehruvian legacy of non-alignment.

The BJP supporters are hoping that making the Netaji files public will further embarrass Nehru’s supporters, especially if the files confirm that Nehru endorsed the spying on Netaji’s family.

The second reason for the decline of Nehru is directly linked to the manner in which the Congress has sought to monopolise his legacy. Whether it is the ritual of renaming stadiums and government schemes after Nehru, the Congress has used its long period in power to uncritically examine Nehru and project him as an icon who belongs to a particular family and party and not the national leader that he truly was.

As the sociologist André Béteille has remarked (as quoted by historian Ramachandra Guha), “the posthumous career of Nehru has come increasingly to reverse a famous Biblical injunction. In the Bible, it is said that the sins of the father will visit seven successive generations. In Nehru’s case, the sins of daughter, grandsons, granddaughter-in-law and great-grandson have been retrospectively visited on him.”

Beteille is right: Nehru is seen by today’s generation almost entirely through the prism of his heirs. Ironically, there is scant evidence to suggest that Nehru wished to actively promote dynastic politics: Indira Gandhi became prime minister almost entirely by accident as a result of the sudden and tragic death of Shastri in 1966. And yet those who have an aversion to the ruling Congress dynasty target Nehru for every failure: Be it the India-China war or the infirmities of centralised planning with scant appreciation for his role in institutionalising a democratic spirit based on tolerance and citizenship.

By contrast, Ambedkar’s Republican Party has been pushed into near irrelevance in politics. But his legacy is alive and thriving, even if the man himself is reduced to a statue. The rise of vote-bank politics has meant that the Ambedkarite idea of social justice and equality is a powerful weapon to unite millions of Dalits and backward castes. Ambedkar may have challenged a Brahminical Hindu order, but even the upper caste-dominated RSS has been forced to accept the Ambedkar vision, albeit reluctantly (witness the recent statements of RSS sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat on reservations).

Parties like the BSP have made Ambedkar into a god-like figure; even the slightest criticism of their icon can attract a violent response. No party can afford to challenge Ambedkar’s ideas for fear that it will mean losing a large voter base.

There is no ‘Nehruvian’ vote bank to confront those who today heap abuse on the leader, especially in the Right-wing-dominated social media. But there is an Ambedkarite vote-bank that will probably shut down a social media site that takes on their hero. The two great Indians have contributed much to the idea of India as a sovereign republic. It would be a pity if their legacies remain shadowed by political partisanship.