During the 1983 Falklands war, a member of the Margaret Thatcher government angrily described the BBC as the ‘Stateless People’s Broadcasting Corporation’ because it referred to the forces as ‘British’ and ‘Argentinian’ forces instead of ‘our’ and ‘enemy’ forces. When an Argentinian ship was sunk, an incensed Thatcher responded, ‘only the BBC would ask a British prime minister why she took action against an enemy ship that was a danger to our boys’. That is when the BBC director general John Birt is said to have reminded the British prime minister that the journalistic organisation was not an ‘extension of the political authority’; its first commitment was to the truth, not to the nation state.

The Thatcher story is instructive at a time when the ‘patriotic’/nationalistic credentials of Indian journalists and news organisations are under the scanner for their coverage of the violence in the Kashmir valley. The newly minted I and B minister has already warned that he expects ‘responsible’ coverage from the media; army information teams have red flagged any attempt to send out any ‘negative’ news; the social media army of ‘proud Indians’ on Twitter has abusively accused journalists (including this writer) of being ‘terrorist sympathisers’, ‘anti national’ and questioned ones parentage.

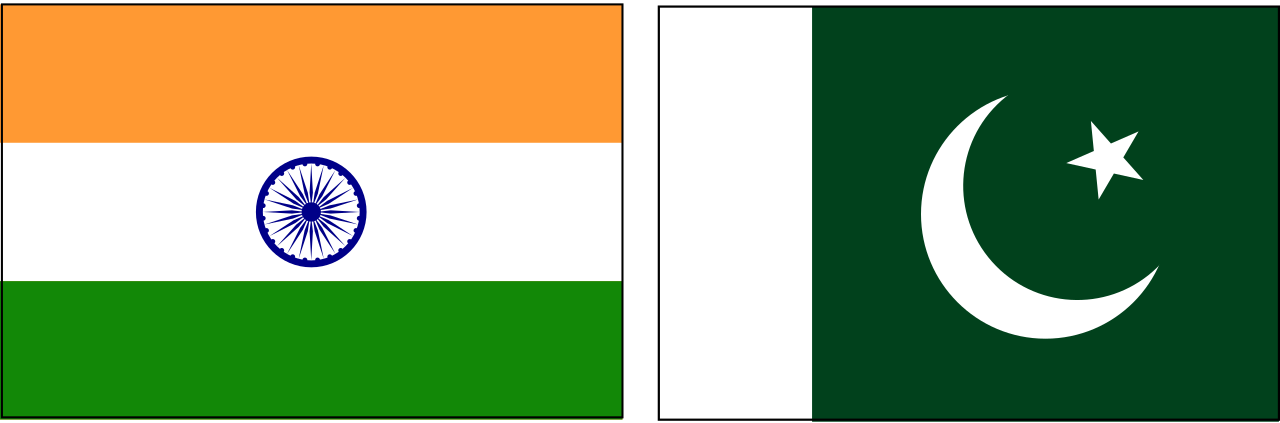

Who is to tell my outraged friends in the Twitter world that journalism in its purest form doesn’t wear the tricolour on its sleeve. Yes, I am a very proud Indian, but my journalism demands that I tell the story of Kashmir, not as a soldier in army fatigues but as a mike pusher who reports different realities in a complex situation. Burhan Wani is a terrorist who has been ‘neutralised’ in the eyes of majority of Indians; he is a victim who has been ‘martyred’ for the thousands of Kashmiris who lined up for his funeral. A propagandist would only broadcast the narrative that suits the agenda of one side but a journalist must necessarily explore both stories: that of Wani the Hizbul terrorist who took to the gun and used social media as a weapon AND Wani as the posterboy for a localised militancy which feeds on tales of alleged oppression and injustice. A journalist must speak to the army which is trying to quell the protests on the street, but must also listen to the youth who have chosen to their vent their anger with stones. And he must then dispassionately and accurately report the ground reality without glamourising violence or terrorism but also without becoming a spokesperson for the Indian state.

It is maintaining this delicate balance that defines good journalism. Sadly, there are few takers it appears for this challenging task. Instead, in a polarised, toxic environment, journalists are being asked to take sides, to state their preferences, to place opinion ahead of facts, to show off their macho ‘nationalism’, to be part of a ‘them’ versus ‘us’ battleground in tv studios and beyond. Which is why I wish to highlight the BBC role in the Falklands war. Here is a genuine public service broadcaster that is able to ensure that its commitment is to the British people, not to the government, even in a war between countries. The philosophy is clear: the truth, however inconvenient it might be for the power apparatus, must be told.

In Kashmir too, we need to tell truth to power: the truth of disaffected youth with limited opportunities for growth, of failed, corrupted politics, of an unshaken ‘azaadi’ sentiment, of army excesses, of a neighbouring country which sponsors terror, of a nostalgic notion of Kashmiriyat which was eroded when Pandits were driven out of their homes, of radicalised youth seeking to romanticise violence, of hard working twenty somethings topping the civil service exams, of an unacceptable distinction between terrorists and freedom fighters. As a vibrant democracy, we must be able to look into the mirror with confidence and face these competing ‘truths’. Too many of the stakeholders in Kashmir, Delhi and beyond have lived in denial for too long. Wani’s killing and its aftermath must end this mood of denial even as we in the media must learn to stop playing patriot games.

Post script: Many years ago, while reporting a story on Kashmir, I described those who had targeted a bus as terrorists. That evening, a local colleague in Srinagar suggested that I might be better off calling the perpetrators as ‘militants’. I asked him why. “Sir, they maybe terrorists, but here it is safer to use the word ‘militant’.” When even simple wordplay can get tangled in the minefield of Kashmir’s bloody politics, you realise the complicated nature of the journalistic challenge.