Having spent more than a week in Gujarat –a state that I regard as both karmabhoomi and Janmabhoomi –over three recent trips, here are ten takeaways from an election battle that seems to have consumed disproportionate news space in the last month.

A) Narendra Modi is still Gujarat’s neta number one by some distance : It doesn’t need a field trip to realise that Mr Modi towers over all others within his party and the opposition. It is now three years since Mr Modi left Gujarat, but the affection and goodwill for him remains intact, cutting across class and caste groups. Except minority dominated areas and Hardik Patel strongholds, it is difficult to find a harsh word being said about Mr Modi (ok, so a group of diamond traders in Surat called him a ‘sapno ka saudagar, and I met one textile shop owner who used the word ‘feku’ but very little else by way of personal attacks). This is a remarkable achievement for a leader who is, in a sense, aiming to win a fourth consecutive election in Gujarat on his individual charisma. The prime minister’s rhetoric is shrill, often loose, and at times smacks of desperation (to bizarrely drag in Pakistan and suggest that Islamabad wants Ahmed Patel to be chief minister of Gujarat was a particularly low blow that brings down the credibility of the prime minister’s office), but Modi is still the son of the soil, a leader who knows how to emotionally connect with his audience, especially when playing ‘victim’ and saviour of Gujarati asmita, and, to that extent, remains the BJP’s brahmastra.

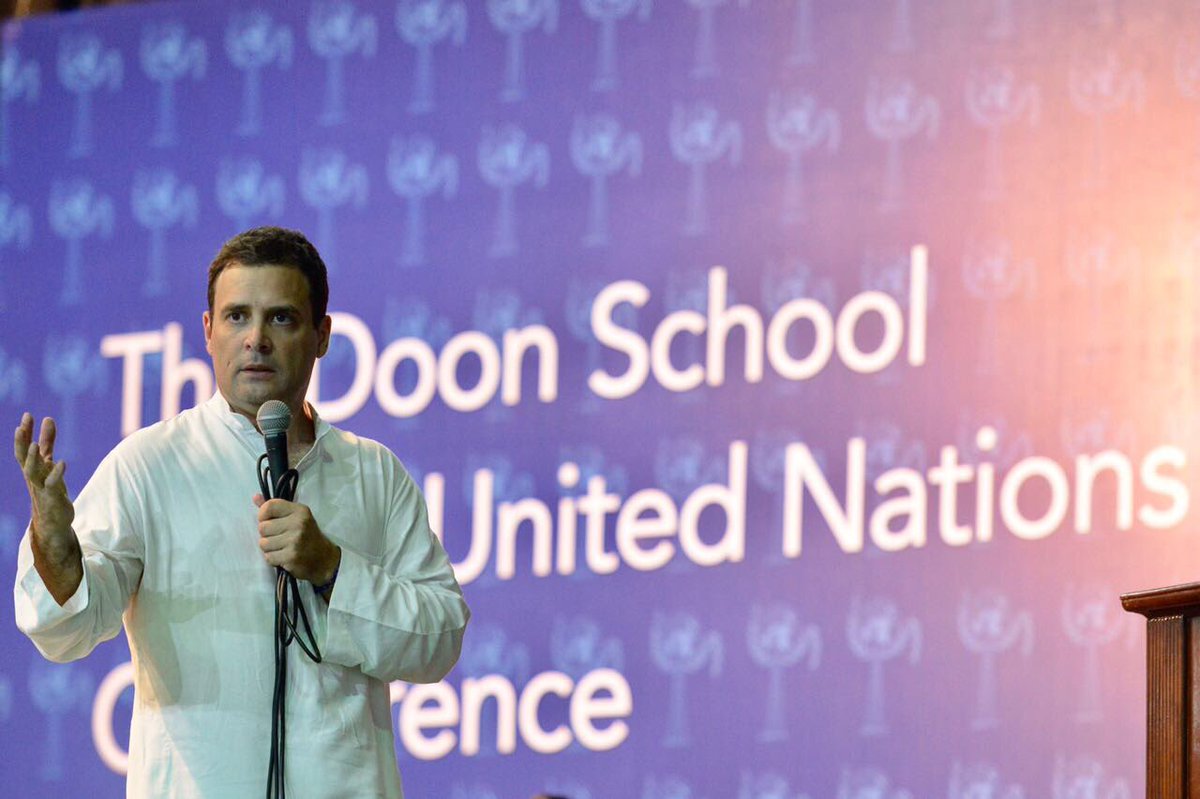

B) Rahul Gandhi has found a voice in Gujarat: the jury is still out whether Mr Gandhi has it in him to be a 24 x 7 x 365 days politician but even his worst critics can’t deny that Rahul has surprised us with the energy with which he has campaigned in Gujarat. His speeches may lack an oratorical flow (he still uses crazily long English words like ‘contradictions’ in rural Gujarat) and the content is fuzzy (Rahul’s answer to most problems seems to be to provide a basket of freebies, from loan waivers to unemployment allowances) but in the heat and dust of Gujarat, Rahul has demonstrated a more intangible human quality called ‘sincerity’. In normal times, this would be taken for granted in a public figure. But in a political universe where demagoguery rules, Rahul’s softer, kinder approach of claiming to be a good listener rather than a big talker (man ki bat versus jan ki bat), has struck a chord. He has even offered a possible template for a future non-Modi opposition nationally by ceding space to regional leaders. Team Rahul has always had a better chance of taking on Brand Modi than an individual personality driven contest and Gujarat could well be a pointer to 2019.

C) Hardik Patel is the X factor in this election: make no mistake, without Hardik playing the dramatic street fighter role, this election in Gujarat may have been yet another tepid no-contest between a triumphant BJP and a timid Congress. Hardik has given the opposition campaign in Gujarat a ‘zing’ that we haven’t seen in years. He has the indefatigable fighting spirit of a Mamata, the chutzpah of a Kejriwal and the sharp edged rhetoric of a Bal Thackeray. The BJP may dismiss Hardik as a ‘lumpen’ (mawali is the precise word one BJP leader used) but when was the last time you saw a 23 year old ‘mawali’ give sleepless nights to India’s premier national party? Hardik’s ability to translate his crowd appeal into votes is uncertain (the Patels are split wide open, the older generation and higher income groups disinclined to shake their loyalty to the BJP) but what is clear is that Hardik has dispelled the fear factor in Gujarat politics that prevented inconvenient questions from being raised and from challenging the Modi-Shah duo. Win or lose, Hardik is proof of a still vibrant Indian democracy’s unique ability to throw up mass leaders — howsoever polarising and divisive they may seem to elite groups — from the most unlikely personal life situations (five years ago, he was handling the local Viramgam MLA Dr Tejashree Patel’s social media outreach from a small dispensary room).

D) The Gujarat model is under strain: it reflects poorly on the state of the Indian media that in the 12 years when Mr Modi was in power, we never really seriously interrogated the Gujarat model of development. Ironically, with Mr Modi not in Gandhinagar, the ‘model’ now finds itself being questioned at last. To dismiss the model as hype created by ‘perception management’ (perhaps a better word than marketing) as Modi critics tend to do would be wrong; to celebrate it as some magical transformation of Gujarat into a ‘vibrant’ heaven as cheerleaders (especially industry) often do, is just as incorrect. Gujarat scores strongly on physical infrastructure (the roads keep getting better, power maybe more expensive but is available in most areas, Ahmedabad BRT is very successful) but starts to seriously taper off when it comes to social indices and the service sector. Sanand, home to the Nano factory, is an example of Gujarat’s skewed development. Almost all the jobs here are now with ‘outsiders’ because many Gujaratis simply lack the soft skills — English education, IT and management training — to compete effectively in the marketplace. By virtually outsourcing health and education to the private sector, the Modi model has given the opposition a potent weapon of targeting the government for ‘commercialising’ crucial public services. Moreover, by handing out major government projects to a handful of industrialists, in a classic case of crony capitalism, the BJP tag line of ‘hu chu vikaas’ (I am development) is now being threatened by the notion of ‘kiska vikaas’ (whose vikas?).

E) Sharp rural-urban-sub-regional divide. No election in India should be ever covered by only visiting the big cities. In a heavily urbanised state like Gujarat, it is particularly easy to get carried away by the flyovers and shining lights of an Ahmedabad or a Surat. The BJP will win a majority of seats in Ahmedabad despite the Patel factor; it will have limited losses in Surat despite anger over GST. The cities are a BJP citadel, but just travel 100 kilometres into the interiors and there is a ‘new’ Gujarat that greets you. OK, so it’s not as bad as an Amethi, but that is not a comparison that sits easily with rural Gujaratis any longer. They can see the gleam of their own cities and draw a sharp contrast with their plight. Sadly, the panchayat system appears dysfunctional: almost every villager we spoke to in north Gujarat districts had a complaint about his local panchayat or council. Not surprisingly, rural Gujarat, especially Saurashtra where farmers have suffered from agrarian distress and low minimum support prices, offers the best chance for the Congress to make major gains.

F) It isn’t just about GST or De Mo, it’s about business interrupted. The Gujaratis love their dhokla, their ‘dhandho’ and their politics, probably in that order. It was easy for the BJP to win UP in the aftermath of ‘note-bandi’ by stirring a rich versus poor divide: UP’s poor were convinced that the rich were being taught a lesson and their black money would be seized. In Gujarat, it is different because everyone wants to be part of the wealth creation juggernaut. In a trader driven society, ‘len-den’ is a daily ritual; the future is often expendable.For the Gujarati trader and those engaged in small and micro enterprises, notebandi and then GST were a double whammy. It isn’t just about the impact on business bottomlines: in a state where the entrepreneurial spirit thrives, state power or ‘tanashahi’ is frowned upon. The anger is perhaps greater because a central government headed by a fellow business friendly Gujarati didn’t listen to their grievances. It’s an anger that gets easily transferred to a state government headed by a nondescript chief minister. ‘Ahankar’ (arrogance) is a word we hear often against local BJP MLAs, many of whom have been elected on multiple occasions (there are 58 seats which the BJP haven’t lost since 1995).

G) The tag line is ‘vikaas’, but Hindutva remains the overpowering sub-text. In 2002, there was James Michael Lyngdoh, in 2007 there was Mian Musharraf, in 2012 there was Mian Ahmed Patel, in 2017, there is Mughal dynasty. In every election, there are warnings of a return to ‘Latif Raj’ under Congress (a reference to Ahmedabad’s don of the 80s) ‘ and, of course, that eternal promise of a Ram Mandir. In no other state is the attempt to polarise communities so easily and coarsely legitimised as it is in Gujarat. The well being of the state’s 10 per cent minorities don’t seem to matter as Gujarat’s Muslims have gone missing in this election . The Congress is silent on their plight for fear of being branded pro Muslim and losing the Hindu vote (hence, the need for Rahul Gandhi’s temple tourism); the BJP is aggressive because it needs to win the Hindu vote. Modi may be vikas purush when he travels to San Francisco but on the west coast of India, he is Hindu Hriday Samrat, preying on the fears and prejudices of the majority community. Those fears may well still prove crucial in central and north Gujarat where scars of the 2002 riots have divided communities.

H) In Gujarat, caste matters, but is not decisive. For the last few days, I have been reminded how Hardik Patel is a Kadva Patel so the Leuva Patels won’t back him; how Alpesh Thakore won’t be able to deliver the Thakore votes in north Gujarat; how Jignesh Mewani has given the Congress an upper hand among Dalit voters and how the BJP has seriously dented the Congress base among Adivasis. All of the above may be partly true, but to locate a Gujarat election through the prism of caste would be a mistake. The Kolis of Saurashtra may vote very differently to the Kolis of South Gujarat, Dalit and tribal votes too could get split while giving an Alpesh Thakore far more seats than his ground strength may well be a decision the Congress will live to regret. This is not the 1980s where the Congress’s KHAM caste-community alliance was invincible. Just like the BJP needs Hindutva plus politics now to expand, the Congress too now needs a caste plus voter base to grow.

J) So, to the big question: who who will Gujarat? If you asked me this question a month ago, I would have almost unhesitatingly said the BJP to be atleast 120 plus seats in the 182 member assembly . If you ask this question to me today, I will press the pause button this time, think a bit and then once again maintain that my instinct is that the BJP remains in pole position to cross the half way mark. The fact is, Gujarat is the original Hindutva fortress, a state where the party led by national president Amit Shah has built a formidable organisation right down to the last booth worker. By contrast, the Congress in Gujarat has remained a moribund and leaderless organisation, one that was mysteriously revived only in August this year when its leader Ahmed Patel was battling for his political future in a Rajya Sabha election. The Congress booth management has been well handled this time by a few tough retired police officers but the vote share gap between the BJP and the Congress appears far too wide, especially in urban areas, to be bridged easily. Yes, there is an anti government under-current in rural Gujarat but the party’s strong and resilient support base amongst the urban middle class and young voters means that the demographics of Gujarat still heavily weigh in the BJP’s favour. And then, of course, there is Mr Modi himself, still teflon-like on home turf. I will say this though: an election which seemed like a comfortable walk along the lovely Sabarmati riverfront is going down to the wire. As a journalist who relishes tracking elections, you can’t really ask for more!

(Post script: my tenth and final takeaway: As you might have noticed, I have not mentioned EVMs anywhere in this article. Despite the worrying complaints, in the absence of hard irrefutable evidence, I refuse to accept that EVMs are being tampered with. Only losers complain of EVM manipulation, and in India’s multi party democracy, today’s loser in one state could well be a winner in another!)