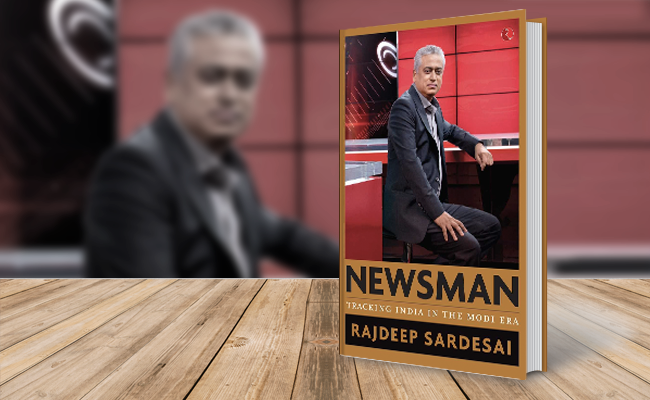

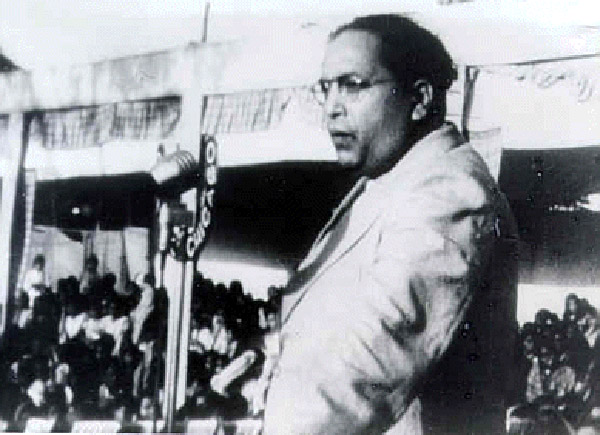

In his most in-depth interview to date, well-known TV journalist and anchor Rajdeep Sardesai spoke about his complicated relationship with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the crisis of credibility in the media, being the favourite target of online trolls, how it has been tough getting over the break-up with CNN-IBN and why it is factually incorrect to label him a ‘Congressi’.

Your chat with Lalit Modi was perhaps one of the most talked about news interviews of the year. After talking to you, he was forced to shun all TV interviews. Do you think the interview damaged his prospects?

I don’t think it damaged his prospects, but it surely showed up Lalit Modi and the Indian establishment for what they are. Here’s a person who’s “most wanted” on Indian shores and ministers are being asked to resign on his account. All this while he’s sitting in the luxury of the Aman Hotel by the Adriatic Sea!

To my mind the contrast was striking and ironical; it was almost a parody on Indian politics. Someone is living a life of luxury in a foreign country, while back home he’s being called a fugitive – while possibly nothing’s been done to bring him back all these years. The interview exposed this aspect for sure. Did it incriminate him? That only time will tell. However, Lalit Modi is a man who’s made it clear that if he goes down he will take others with him.

There is a perception that the media backed off after t Modi named names.

That’s rubbish, I don’t think the media has backed off; every story has a shelf life. A story sustains itself based on the credibility of the people at the heart of the story. If Lalit Modi is able to back all he says with hard evidence, then the story will stay relevant. If Modi tweets and scoots and then expects the media will stay on the story, it’s not going to happen. He will have to back all his claims with hard facts that incriminate people, or face the heat himself as the ED goes deeper into his dealings.

Finally, there’s no resignation forthcoming, so did the opposition fail in building pressure on the BJP over LalitGate?

I think LalitGate was used by the opposition to build a perception against the government. A government whose prime minister had said, “Na khaoonga na khaane doonga” (I won’t take bribes and won’t allow others to), was for the first time, finding itself on the back foot over the issue of propriety. So the opposition got a handle to beat the government with, especially before the monsoon session of parliament.

In terms of perception, the opposition has achieved what it wanted. Interestingly, I think Lalit Modi, too, achieved what he wanted: that he can’t be singled out for his acts, that many in the BCCI and the opposition were also in on it. Meanwhile, the BJP, too, by its strategic silence and unyielding stance also has sent out a clear message: that the media will not dictate the agenda of this government. The PM has made it clear that he’s not Manmohan Singh and will not sack ministers depending on what the media is broadcasting. Will this rigid position harm the long-term perception of the party? That remains to be seen.

Recently Akshay Singh from the India Today Group died under mysterious circumstances while covering the Vyapam scam. Two journalists were also set on fire because they dared to take on politicians and the mining mafia. Has the media lost its ability to work together to generate pressure on the system?

I don’t think so. Look at the Lalit Modi and Vyapam cases. There is a lot of concerted media noise. Of course, you will have the occasional one-upmanship; it’s unfortunate, but it happens. My bigger problem is: Does it take the death of a journalist for us to realise the scope of the Vyapam scam?

The acronym Vyapam stands for ‘Vyavsayik Pareeksha Mandal’ but perhaps it’s not seen as good TRP material! Then there is what I call the tyranny of distance; something that happens so far away from Delhi rarely excites the media.

So we in the media have to ask ourselves: did it have to take the death of a journalist for Vyapam to become 9 pm news? Similarly the death of Gajendra Singh at Jantar Mantar made farmer suicides prime-time news. While such deaths happen daily and are rarely covered, we in the media also have to ask ourselves the tough questions. What does it take for us to realise the importance of a story?

Are journalists under a lot more threat today?

Journalists have always been under attack. We register something when it happens closer to Delhi. But take a look at far-flung areas of India and you will see regular attacks happening. Today, journalists are not only under threat from the gun, but also from a section of people who want to take down the media. On our part, we have to ask ourselves why we have allowed ourselves to face this deeper credibility crisis that makes us soft targets today. Do we stand up united when the profession is under attack? I remember when the Shiv Sena had attacked the IBN office five years ago, many channels didn’t run the story, because the ‘competition channel’ was under fire.

When you say that journalists are not under threat from the gun alone, are you hinting at social media? Has all the negativity of Twitter affected you personally?

I guess anyone would be. If there is a large army out there that has decided to take down Rajdeep Sardesai, at some stage I will be affected by it. That said, I also take pride in the fact that I have been able to get under the skin of so many people. The worst thing that can happen to a journalist is being ignored. So if there is a large section on social media that follows me and yet wants to target me, I treat that as a badge of honour.

Just like anyone else on social media, I have a right to dissent. But you don’t have the right to abuse me. That has been one point that I am unable to get across to the multitude of people who live under the garb of anonymity or are part of ‘armies’ who are immersed in doing bhakti of their party leaders.

The prime minister recently called a meeting of 150 influencers on social media, many of whom were habitual abusers on Twitter. Does this ploy of calling select followers and asking them to behave work? After all, the BJP’s track record of getting the various Senas to fall into line hasn’t been great.

No, they never have, and at the end of the day, leaders have to realise that they are judged by their followers. I am not saying that Modi is actively encouraging his followers to indulge in this kind of behaviour, or that Arvind Kejriwal and Rahul Gandhi are asking their followers to abuse others, but the fact remains that it is happening. This reveals a growing intolerance in society and the unwillingness to have a genuine dialogue. On Twitter, there is no dialogue. If Modi has asked his followers to stop the abuse, it’s certainly not working.

Those who use words like ‘presstitutes’ must realise that they are tarnishing an entire profession. When the prime minister himself uses words like “news traders”, then it almost gives a licence to his followers to abuse. Yes, there is a credibility crisis, but to label professionals as “news traders” because some of us haven’t stopped asking questions is crazy.

Do you think a lot of trolls are organised?

(Laughs). Well, either Indians have a lot of time on their hands or this is extremely well-organised and well-paying for a few. I am sure it’s organised. Look at the manner in which trends are built systematically, be it feku or pappu. What this has done is bring down the quality of conversation in social media and to reduce it to one-upmanship.

Does Twitter punch far above its weight? It just takes a few hundred tweets to build a #trend, and then it manages to influence newsrooms about what stories to follow.

Of course. I believe these days, companies can fix trends for you, and if newsrooms are getting influenced by social media trends then it’s terrible. Twitter is a double-edged sword; it can be a great source of dialogue and information that can deepen democratic practices or it can be a noxious chamber of hate and anger that targets people and builds enemies. Twitter now needs to decide what it wants to be.

After May 2014, has the media space changed in India?

Nothing changes in a year. It is a continuing process. There has certainly been a decline in quality and there has been a growing tendency of the ruling dispensation to either co-opt or coerce the media to toeing its line. In that sense, it’s a big worry.

But the credibility crisis is the biggest issue for us, and we have to answer for that. We have to ask whether we have become arrogant as media persons. We were supposed to be the cockroaches, always on the hunt to ferret out news. We are not the badshahs. We are the ones who question the badshah.

In the past year, we have been happier taking selfies with the prime minister than asking him questions.

After your farewell speech, some of your colleagues asked you to start a venture of your own and you said that you thought CNN-IBN was your own. How hard has it been for you to let go of a channel that you built from scratch?

It has been very, very difficult. It still has not fully sunk in. But then you have to move on. Strange how suddenly things hit you. Phil Hughes died on the cricket field playing the game. I was watching it and I said to myself, “Here I was agonising about what happened to CNN-IBN and there was a guy who was playing the game he loved, and he died.”

While the parting has been emotional, personal and difficult, I tell myself that worse things could have happened. So I try to gripe less now.

Do you think that your exit was inevitable after Reliance took control of CNN-IBN? Was the Google Hangout with Kejriwal just an excuse for executing something that was already in the works?

I have no idea. These questions should be asked to Raghav Behl and to Mukesh Ambani. I am a professional journalist; for twenty-seven years, that is what I have done. I am not a businessman, so for me to analyse this call is difficult. Maybe the proprietors wanted a particular kind of editor. Maybe I was not that kind of person.

Maybe because you would have proven to be non-conformist in your ways and in your political views?

I believe that newsrooms are where ideas are contested, where a reporter can walk up to me and say, “Sir, you are wrong.” I don’t think a newsroom is a place to be a dictator or where business interests collide with the news. There are editors out there who are hatchet men of corporates or are simply there because they are pliable. You said conformist? Well, I am certainly not a pliable person.

Has the incident made you more disillusioned with the profession you have been associated with for so long?

Over the past year, I have become more philosophical. A year ago, I was far more idealistic, but my idealism is being battered by what I see around me. Maybe I am a dinosaur in today’s media world, especially with all this grey hair.

Dinosaur? But then you will invite the charge that you are not relevant any more.

That is for the viewer to decide. But my core journalistic principles will not change. That much I am clear about. I will still be excited by the breaking news story and a big story that will shake the system, but my cynicism stems from seeing the kind of compromises people around me are making in the industry, compromises to stay “relevant”, as you put it.

Fair point, but even as you remain uncompromising in your principles, are you physically dried and dusted to do what you have been doing all these years?

Well, if I were tired, then in the past nine months I wouldn’t have been able to put a book out, market it aggressively and play a small role in the re-launch of India Today Television. So I am not tired, or retired. I am just older and wiser. If a story breaks, like LalitGate, I will stay up all night, reach Montenegro, do whatever it takes, negotiate with Serbian camerapersons who don’t get English, but still get the story in.

In your book, 2014 The Election that Changed India, you have said that you’ve been as neutral as possible on Modi and kept the focus on the campaign he ran. How difficult was it for you to remain neutral after covering what you have in 2002?

The book is my evidence on where I stand on Modi, the positives and the negatives. I believe that a book is something that is lasting and permanent. I have thought long and hard about it and I have put it all down.

I have admiration for all politicians at one level, but as an observer I have the right to question them and critique them. For example, I believe Modi is a 24×7 karmayogi politician; at the same time I also believe that he hasn’t satisfactorily answered a lot of questions on 2002. I also may have questions about the ideology that Modi represents but at the same time I have respect for the fact that he’s someone who’s come through the hurly-burly of politics in this country. Similarly, I believe that Lalu Prasad was one of the flag-bearers of the Mandal agitation that changed Bihar’s landscape. That doesn’t mean I don’t have the right to criticise him for bringing in family raj and criminalisation of politics in the state.

Have I got emotionally entangled with the Gujarat riots? Possibly yes, because that was and is a story that I have strong feelings about.

If your coverage of 2002 defined you, has your reportage on Modi shaped your image of how you are perceived as a journalist?

Maybe. Please remember this is also because in the past decade Modi has played a large role in the national media discourse and not just my journalistic discourse. From a politician who used to come into our studios [as a BJP spokesperson] at 30 minutes’ notice to the politician whose India’s number one neta, it has been a remarkable rise.

I have followed the Modi story and can claim to have a bird’s eye-view of the story and an understanding of the man. As a result have I got too closely identified with Narendra Modi? May be.

There seems to be a power play going on between the two of you. At the HT summit you questioned him on his changing the development track. He retorted with a comment on the saffron colour of your kurta. In the election campaign, you interviewed him seated on the footboard of a bus, while Modi towered over you.

He and I shared a good journalistic relationship for a very long time. We had a constant dialogue earlier. He was also one of the first people to call me when my father passed away.

While the relationship had its ups and downs, I have always seen it as a journalistic relationship in which I am an observer, a critiquer. Unfortunately, society got polarised. You cannot be an objective observer any more; either you are a bhakt or you are a permanent critic. What if I am neither?

You view this as professional from your side, but has Modi been personally affronted by your journalism, questions and critique?

I don’t know. That’s a question you have to ask him. From time to time, I am told he has taken offence, but the Modi I knew appreciates the fact that there will be times when a journalist will be a critic, while there will be praise as well. A negative comment doesn’t mean that there is breakdown in the relationship.

I keep saying this. Modi became the PM. Mai to wahi ka wahi reh gaya! Mai abhi bhi raat ka show karta hoo, jo 15 saal pehle karta tha. I have remained where I was. I am doing the same night show that I did 15 years ago.

What happened at Madison Square Garden? Did you misjudge the crowd? Did you think this couldn’t happen in America?

I should have walked away from the incident. I shouldn’t have got into a slanging match. It was unprofessional of me. I have accepted that. However, I stand by the questions I asked. Modi was in the US, we were having a big show in Madison Square, in the same country that had denied him travel documents for 11 years. Isn’t it valid to ask whether the US was in the wrong for so long?

Was it a valid question to ask, given the situation of frenzied fans?

They could have been frenzied fans, but I was not there as a cheerleader. A journalist doesn’t become a cheerleader because there were frenzied fans all around. They didn’t recognise the value of a journalistic question. I didn’t know that they wouldn’t recognise that. But if this was Gujarat there wouldn’t have been a single problem.

You are saying you can raise these same questions in Gujarat without any issues. Are you sure?

I am sure. NRIs have another worldview. I have done all kinds of live shows in Gujarat. I just did a show in Gujarat for my book where we raised similar questions. It went on for so long that the organisers had to extend the programme. Combative questions were being asked.

Long-distance nationalism is a dangerous thing that affects NRIs, because you can sit in a plush AC villa in Texas and believe that you are more patriotic than me, when I have to breathe Delhi’s polluted air while going to office and deal with the real India here. That makes them lose their perspective.

There have been a lot of changes for Modi too in the past year. From invincible to charges of Maun-Modi (Mum Modi), how long can the PM shun the media?

Narendra Modi is a very sharp man. Manmohan Singh’s silence was forced because he didn’t have real power. When it comes to Modi, the silence is strategic. Everything that Modi does is strategic. The opposition will see it as a weakness and play it against him. Will they succeed? We’ll see four years from now, but Modi would rather have his spokespersons take on the opposition right now and not get into a tu-tu-mai-mai (tit-for-tat) battle.

That said, this one-way communication through Mann Ki Baat, Twitter, Facebook, selfies, is a gamble, because after a certain point people may start saying that bolta hai, lakin karta nahi hai (he talks, but does not act), or begin to notice that he doesn’t talk about the really controversial issues.

Manmohan Singh didn’t have control and wasn’t a great communicator, but Modi has both; yet he’s not given a single sit-down interview in the past year.

We keep saying Maun Mohan, but every time he used to go abroad there were press conferences on board the PM’s aircraft. In his first two years Singh organised two large press conferences at Vigyan Bhavan, where he took direct questions from reporters.

Contrast this with Modi’s record when he was CM for 12 years. He never held a single press conference where he could be questioned by journalists. That is Modi for you. But he’s a very good one-way-communicator, one of the best we have, so he never felt the need to get into a two-way street. Even when journalists do get a chance to quiz him, like at the Diwali Mela last year, we didn’t ask questions. We were too busy taking selfies with him.

A lot has been said about your political leanings as well, so according to you, which party’s ideology is best suited to run this country?

I am basically a congenital critic, so I see a weakness in all parties. I truly don’t see anyone who fulfils my dream of a liberal, democratic, pluralistic, meritocracy-driven India. All parties fail on one or many of these four basic criteria.

But there have been rumours of you joining a political party, even getting an Rajya Sabha ticket.

At various stages, one meets with politicians as a source. Some say, “Come join us!” I have always resisted this because it is a trap. The day you give the political class a sense that you want to join them, you are done. I have seen some first-rate editors and journalists. The moment they became part of the establishment, their journalistic core withered away.

But for you it’s never-say-never on this?

Who knows what tomorrow brings? If you would have come to me 14 months ago, we would have been discussing future plans of CNN-IBN. Now we are talking about it in the past tense. But when Walter Cronkite was asked about a political future, he said, “I haven’t done 40 years of journalism to join a political party. I did it because I loved politics and the news.” That is my core belief as well.

Do you think your liberalism and pluralistic values got you tagged as a ‘Congresswalla’. Vinod Mehta faced the same allegation too.

In a polarised world this happens. If you are not with Modi, then you must be a Congressi, or the other way around. May be in hindsight, I should never have accepted the Padma Shree from the Congress government. I don’t think journalists should accept state awards. In hindsight, it was a mistake. I think Vinod and I had the same journalistic values as we came from the Mumbai school of journalism, which teaches us to be deeply sceptical of the political class and treat them with irreverence.

At CNN-IBN, we did the big story on the de-freezing of Quattrochi’s account. How come we were not seen as anti-Congress and pro-BJP at the time? When we did a story on the mining mafia in Karnataka, the BJP government there targeted us. When we forced a Samajwadi minister to resign, the party summoned me to the assembly, accusing me of a breach of privilege. When we exposed Mayawati in the assets case, our OB van was burnt. So these charges of belonging to a camp or a party are tools to intimidate a journalist or an editor to fall in line with the cheerleaders on both sides.

Even in cash-for-votes, I had the Congress accuse me of being hand-in-glove with the BJP and the BJP accusing me of being pressured by the Congress. The fact is that the entire sting was put out in the public domain once we were ready with all the journalistic checks. Yes, we could have handled the issue better in hindsight but to accuse us of being partisan is unfair when you look at the body of work over a period of time.

You views on the declining standards of news media are not a secret. Where do you think news went wrong and is there a reason why the profession attracts so much of negative criticism and ridicule today?

While there is no one point when this crisis hit us, there is a fundamental problem in the business model of news television, where we spend less on news-gathering today than we did ten years ago. The number of channels have gone up, and so has the competition, but revenues and viewership have remained stagnant while costs have increased.

Second, because advertising revenues are linked to TRPs, news is being governed by what will sell and not what should be aired. A farmer’s suicide will not sell but Hema Malini’s accident will. Third, I guess we have lost our moral compass. Why did we become journalists? To inform [the public] or to sensationalise? This is a question that has to be asked by editors and owners because they are ones who take the real decisions. That is where the real responsibility has to rest.

I think we need to spend more time on mentoring and working with young journalists; otherwise, we will rapidly become a stagnant pond.

The race for viewership and TRPs is unlikely to change, so what are the chances of quality television journalism surviving? You have often spoken about a trustee model for news TV.

I am hopeful that in the next five to ten years we will have a subscription model or that a trusteeship model will ensure that television emerges from the situation it finds itself today, that there will be space for niche, high-quality journalism that won’t be influenced by proprietors or TRPs.

The problem is how many people in the industry, government or media are ready to invest in a trusteeship with the sole purpose of creating a genuine public service broadcaster? This is a tough call for India, where we find a large section of media either allied with or co-opted by the government. The space is shrinking for truly independent media that can question the government.

While the fourth pillar of democracy is expected to live up to high standards, the constitution itself does not give the media any rights or protection. Is that not a contradiction?

While there is no institutional mechanism to protect or fund the media, let’s not forget that over the past few decades, big stories and exposés have come through the media. Accountability to a large extent still comes via the media. We may be feared more and respected less today, and we have to ask why we have put ourselves in this position. But I disagree when it’s said that the media is not going its job. Despite all its problems we have a vibrant press in India.

Individual reporters have great integrity in this country. My bigger problem is with owners and editors. It’s their integrity that I call into question. If there is still independence in the media, it is because of the reporters who are still pushing the system with their idealism and drive for the big story.

What is your Frost-Nixon moment? Or is your finest hour in journalism still to come?

Ah! This is not for me to answer. Let the viewers decide this. But I can say that launching CNN-IBN in December 2005 gave me great professional satisfaction. So did live election programming with Prannoy Roy and Vinod Dua, and breaking the story of Sonia not becoming the PM and covering the Mumbai blasts and riots of 1992-1993 as a young journalist.

So there is no one moment. I follow the RK Laxman recipe of making great cartoons every day for forty years, i.e. to treat every cartoon as your first one. That’s what I try to do and that outlook sustains you.

Is news your first love or are there others?

Let me see. First comes family, kids and friends. I really value them. Then comes cricket and sports. Then comes music, followed by food. Somewhere along the way there’s news. There, too, I battle between the charm of the printed byline and breaking news on TV.

You are a son of a famous cricketer and you studied law. Why journalism?

When you are not good at other aspects of life, you become a journalist. But seriously, I wanted to become a cricketer but wasn’t good enough. I went to the Bombay High Court for six months and realised it was not working for me. I used to write for Behram Contractor’s The Afternoon Despatch and Courier. I just loved the sound of the typewriter and the newsroom and that’s what drew me to journalism. That was 27 years ago.

You were the first poster-boy of TV news. Rumour has it that it took 18 takes for your first piece-to-camera. True story?

It was a lot of takes for sure. My first TV story involved chasing down Brian Lara, who had broken the record for hitting the most runs, and I barely got it right. I was not comfortable with TV for a very long time. May be I am still not comfortable.

Your nightly song tweets are getting more popular by the day. How does that happen?

I always listen to songs on my drive back home. That’s when all the classic Hindi hits are playing. I am a great FM listener and I pick one of these songs. Sometimes the songs are linked to what is happening in the day; often not. Whenever I am low, Hindi retro music really gets me going. In fact, I commented the other day that it would be better for me to do a 10 pm show on radio called Rajdeep Ki Farmayish than the [contribute to the] noise of news every night. Maybe we need to evolve beyond the noise.

What beyond noise? After all, the 9 pm fights won’t last forever.

News evolves. First, we just read the headlines on DD, then Prannoy came in and give it depth, Arnab gave it a pugilistic angle, but what will last is credibility. Journalism is not a weekly exercise in TRPs, journalism is a journey where every day is a new day. We will continue to tell the story. The delivery mechanism will vary.

I do think that we need to see more positive stories of a changing India on the news. I have made an attempt with a ‘good news today’ segment every night, but we need to see a lot more of that. Also we need solid reporting on health, education, science, environment and gender issues. India is changing. Maybe we in the media are a step behind civil society.

Is the age of the neutral journalist gone? Does an editor or anchor have to take sides today?

It’s a change that is taking place globally. Some organisations have decided that being partisan sells. The idea is, ‘Unless I don’t take a stand, the viewer or reader will be confused, so let me take a strong position.’

When I started out in 1988 in The Times of India, it was made clear to us that the news pages were the news pages. If you had an opinion to express, then you go to the edit pages. Today, you have opinion on the front page as well. Today, television forces an opinion on you, either by the position of the anchor or by the way the story is crafted. We have become partisan and participants in the debate, rather than just observers. While the notion of balance is being lost in this cacophony, I still believe in it as a fundamental principal of journalism. Our job is not to deal with black and white. Every story has its complexities in shades of grey and I believe in exploring those.

I can also see why many people will turn to an editor who takes a strong position, because the stand will either confirm what they already believe in or might be totally contrary to what they believe in, causing outrage and anger.

It indeed is fascinating that two of the biggest names in television journalism were close friends at one time.

We are still friends. I have not parted ways, from my side. One of the happiest memories I have is watching the 2003 World Cup final in South Africa with my father, who was ill, and I wanted him to see at least one World Cup final. My son and Arnab [Goswami of Time Now] were also there and the four of us had a great time.

I think what happens in this crazy, competitive world of television news is that we get caught up in this ‘them vs us’ and even relationships that are based on mutual respect tend to lose their core. But I still see Arnab as a friend.

If you were to end this interview with a song tweet, what would it be?

(Smiles.) One is my life anthem, which I need to follow more: Maein zindagi ka saath nibhata chala gaya har fikar ko dhuen mein udata dhala gaya. Chala gaya. Zindagi ke safar mein guzar laate hain Io maqaam woh phir nahin aate, jaate hain jo maqaam. That’s also my caller tune. The other one is Kishore’s classic, Zindagi ke safar mein guzar laate hain Io maqaam woh phir nahin aate, which I think is the most classic song ever made.

The interview first appeared here