Maybe it’s the skill of prime minister Modi to convert every state election into a ‘national’ battle but never before has an election result to three small states in the north east attracted such media attention. So here are my ten takeaways from the battle for the north east, the first big election verdict of 2018.

1) The BJP is by some considerable distance the country’s premier national party. It isn’t just the fact that the BJP is in power in 21 states, it’s just how rapidly they have expanded their geographical footprint. When they came to power at the Centre in 2014, the BJP was in government in just half a dozen states; from there to their present status in the span of just four years is a quite remarkable achievement. Narendra Modi and Amit Shah must take a lot of credit because they have quite clearly re-invented election strategies: a robust 24 x 7 campaigning style that is relentless and rewarding. There maybe just 5 Lok Sabha seats at stake between Tripura, Meghalaya and Nagaland, and the results may have no impact on the 2019 general elections or the next big state battle in Karnataka in May, but the BJP’s presence in government in all three states gives the Modi-Shah combine the psychological ascendancy once again, a conviction that it remains electorally on a roll (that it has also happened just on the eve of a parliament session is a side benefit in ensuring clever headline management in the times of Nirav Modi and bank defaults!)

2) Tripura is the ultimate proof of the BJP’s formidable election machine, arguably the most effective vote gathering juggernaut in Independent India. To win a state where in the previous election, 49 of your 50 candidates lost their deposit is a swing in fortunes that is unprecedented. No single factor is responsible: a focussed leadership, a strong RSS cadre based organisation, artful booth management, plentiful resources, a strategic if risky tie up with a local tribal outfit, a weakened Congress, a fatigued left, have all come together to allow the lotus to bloom in Agartala. But above all else, it’s the audacity of ambition that is impressive: who would have thought tiny Tripura would be so firmly on the BJP’s radar? In fact, when Amit Shah spoke of the BJP targeting Tripura as a ‘growth’ state a few years ago, there was a measure of incredulity in the response even from those within the party; now, he is seen as a modern day Chanakya! That a cadre based right was able to challenge a cadre based left on its home turf and win must make this victory smell particularly sweet.

3) No election is won by individuals alone. The BJP has a ‘Team’ with Modi as the all powerful general, Shah as his deputy but crucially, enough local level commanders to spearhead the charge. Ram Madhav has proved himself as a man for all seasons from Kashmir to Kohima; Himanta Biswa Sarma is the BJP’s north east army corps commander and the BJP Tripura in charge Sunil Deodhar is the anonymous battalion leader who can inspire troops (karyakartas) into a tough battle. Deodhar, like Modi, is a RSS ‘pracharak’, the kind of nuts and bolts committed organisation man that the other parties so desperately lack at the moment. Deodhar doesn’t want to be Rajya Sabha MP, doesn’t want to be a minister, just is an old fashioned political activist who has put party and ideology above self, spending years building the RSS shakha network across the north east.

4) The BJP has leveraged its four years at the Centre and two years in power in Assam to build a strong equation with potential allies in the North East. The relationship maybe transactional at one level and often leveraged through money power (every north east govt depends on central funding) but by forging a broad North East Democratic alliance, there is a genuine platform which has been created to address grievances. That the PM has himself invested time and personal equity in consciously projecting a ‘look/act east’ policy — holding major central government meetings in a Guwahati and Shillong is one step — has helped build a trust quotient that has made it easier to stitch convenient regional alliances.

5) The BJP has also shown the political ‘flexibility’ to ‘customise’ its agenda to address diverse constituencies. The MIM leader Asauddin Owaisi was once quoted as saying, ‘For the BJP, beef is mummy in Delhi and yummy in the north east.’ He wasn’t wrong. But what the BJP’s rivals will see as duplicity could well be explained as a recognition of a diverse cultural ethos by a party which for the longest time was defined by a ‘Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan’ brand of politics. The dissonance may still rear its head in the future but that the BJP has been able to make itself ‘acceptable’ in Christian dominated Nagaland and Meghalaya is not without significance. Yes, the BJP won just two seats in Meghalaya and is a marginal party in Nagaland, and has ridden to power by ‘deal-making’ with regional parties but there is clearly no ideological isolation or political untouchability of the kind that haunted the BJP in the 1990s. It is interesting that the hill parties of Meghalaya, for example, chose the BJP to form a government with when they had the option of siding with the Congress (even the Sangmas of the BJP’s Meghalaya ally NPP were once a Congress family). Nagaland is less of a surprise: Naga parties have traditionally chosen to deal with whoever is in power at the Centre. Of greater concern here is the Nagaland framework agreement signed with Naga militant groups in 2015 but still not made public and whether the agreement will lead to a more durable peace.

6) The Congress, once the dominant force of the north east, is now a party in retreat. In 2014, the Congress was in power in five of the states in the region; now, it just has tiny Mizoram to show for itself. What happened in Arunachal was morally indefensible but the Congress leadership did itself no favours by procrastinating in a crisis. In Manipur, a strong local satrap like Ibobi Singh atleast offered a challenge. Elsewhere, the party has allowed a familiar rust and decay to set in, symbolic of its overall national health. Tripura is a good example. The BJP made its initial inroads in Tripura primarily because the Congress just evaporated, first taken over by the Trinamool and then the BJP. It’s the 36 per cent Congress vote of 2013 that was reduced to single digits in 2018. The party’s campaign in Tripura never took off, it contested just 18 seats in Nagaland, and allowed the situation to drift in Meghalaya till it was too late. Its general secretary for the north east, CP Joshi has earned the dubious reputation of being a leader who can snatch defeat from victory if required (the Congress has just split in Bihar, another state which he presides over). Contrast Joshi’s lethargy with the raw energy of a Biswa Sarma, the BJP’s Assam-based go getting leader. To think that Biswa Sarma was a dyed in the wool Congressman till just over two years ago is another reminder of how easily the party has squandered its own talent by choosing not to empower those who may challenge the status quo with their ambition and desire.

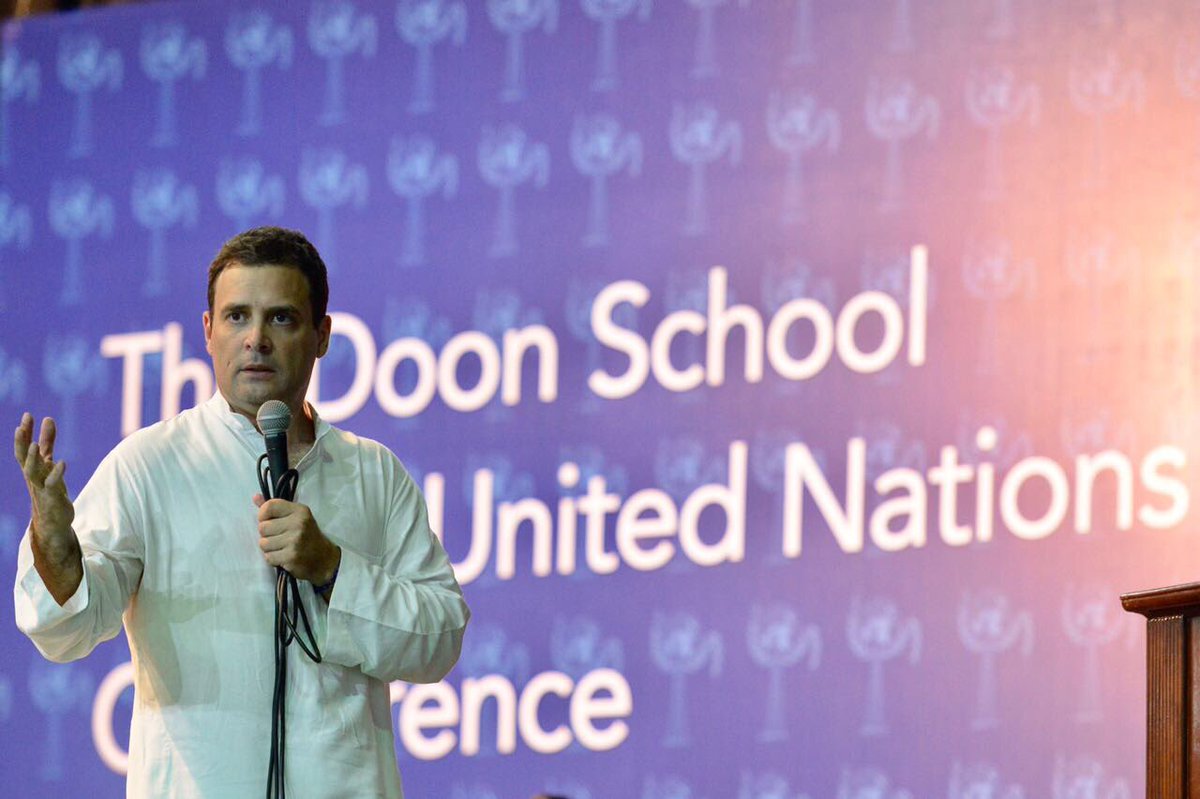

7) After its ‘moral’ victory in Gujarat and an impressive showing in the Rajasthan by-elections, the Congress leadership convinced itself that it was on the right track to recovery. Rahul Gandhi’s ascent to party presidentship was seen as a sign that the first family of the party was back in business. And yet, Rahul Gandhi’s interventions in the north east only confirm the suspicion that he is still a work in progress, alternately confident and casual, a well-intentioned leader still unable to lead aggressively and consistently from the front. Gandhi only addressed one meeting in Tripura on the last day of the campaign and ignored Nagaland altogether. Maybe, it was a lost cause in any case but what is the message to the party workers if the leader gives up so easily? Rahul was more assertive in Meghalaya where the party was in the race but here again he might have been better off spending a full week campaigning in the state rather than dashing off to launch his Karnataka campaign, a state where elections are still a few months away. Perhaps, the final proof of Rahul’s on-off approach to politics was when he chose to spend the results weekend in Italy with his ‘Nani’. Nothing wrong in surprising your grand-ma with a ‘hug’, but surely that could have waited till the election results were out. The optics are once again misconceived: this is a week to be hugging your candidates who have won, grandma perhaps can wait! Rahul’s supporters may insist that time is on their side, but time waits for no one, and maybe running out rapidly ahead of the 2019 general elections. Winning Karnataka (and later in the year, Rajasthan) is make or break for the Congress leadership’s immediate political calculations.

8) Like the Congress, the left too needs to go back to the drawing board. A few months ago, when I suggested to a left leader in Delhi that the BJP might offer a real challenge in Tripura, I was brushed aside: ‘you journalists are easily swayed by Modi-Shah’s media blitz. Tripura is not Gujarat!’ Indeed, Tripura was not Gujarat. While in Gujarat, the BJP was able to fight off a 25 year anti incumbency, in Tripura, a mix of complacency and arrogance meant that winning a sixth election in a row was a bridge too far. Yes, Manik Sarkar was an ‘honest’ politician and we could celebrate his being the country’s ‘poorest’ CM but he was also ultimately a one man show. Yes, he brought peace and stability to the border state, but peace cannot guarantee jobs. As it’s Tripura model unravelled, the CPI M has chosen to blame the BJP for misusing money power rather than look within. Living in denial won’t help the left: its precipitous decline in neighbouring Bengal is a consequence of this intransigent attitude. With 42 per cent of the vote, the left still retains a solid core base in Tripura, but its ideology needs to attract the younger voters in particular to remain relevant.

9) As politics gets localised, every state result must be seen in isolation. An impressive BJP triumph in Tripura for example doesn’t necessarily mean that the party will make similar strides in left ruled Kerala or, indeed, in Bengal, the other potential ‘growth’ state. But there is growing evidence to suggest that the BJP is rapidly occupying the spaces vacated by the Congress to emerge as a challenger to existing political alignments in states where once the Congress was the premier national force. Expect Odisha to be the more immediate potential ‘target’ state in 2019 with Bengal and Kerala also on the radar. And yet, the main challenge for the BJP to remain on top in 2019 is retaining its bastions in north and west India.

10) Personally, the best news for me is the fact that the dramatic rise of the BJP in the north east has forced the news media, and tv in particular, to focus on a neglected region. I have often called it the ‘tyranny of distance’ but the fact is that the north east has been in real danger of falling off the national news map. That it has taken a landmark election result in Tripura to reduce the gap between Agartala and national news headquarters is a positive sign. Hopefully, although I rather doubt it, we will be forced to keep our gaze on the region beyond just another exciting T 20 like election counting day! Next stop Karnataka!